The plotline in the Book of Esther is unlike any other in the Old Testament. Achashverus, the mighty King of Persia, throws a party for the, male only, upper crust of his empire. He commands his trophy wife, Vashti, to come and show her beauty to his guests. She refuses, possibly because she is supposed to show up, wearing only a smile. The king senses the danger in allowing expressions of free will at his court, and banishes the Queen, who goes off to write an extremely successful self-help guide for opressed women. No, actually, I just made up the last sentence. Anyways, the King announces a “Dancing with Kings” competition to find a new and better Queen, to which all good-looking virgins of the empire are “cordially invited”. The title goes to the beautiful Esther, who, unbeknownst to the King, is Jewish. Eshter’s adoptive father, Mordechai, worries about his daughter and hangs around the palace to try to pick up news of how she is doing. When Haman, the Kings trusted right-hand man, leaves the palace to take a little ego-trip, he encounters Mordechai who, unlike all other subjects, refuses to bow down before Haman. Haman goes to the King and asks to have not only the insolent Mordechai executed, but also his entire people. The King, who gets a lot of these requests, absentmindedly agrees.

Mordechai finds a way to get in to the palace and explain the situation to Esther and pleads with her to intervene with the King. No mortal is allowed to initiate contact with the monarch at the risk of loosing their lives. But to save her people, Esther risks all and shows up uninvited before the King.

On the holiday of Purim, Jews read the Book of Esther. It’s the rowdiest day of the year in synagogue, many people come dressed up in carneval costumes, and every time the name of Haman is read aloud, the entire congregation buus or makes noise with special noise-makers. In my heart, I sigh a sigh of relief each year when Achashverus extends his spire to the trembling Queen, and lets her, and my people, live. The situation in Shushan, the Persian capital, is quickly reversed, Mordechai becomes the King’s right-hand man, and Haman is hung on the gallows he had prepared for Mordechai in his back-yard. There are also some marvellous sub-plots, but if you’re really interested you’ll have to go read the original.

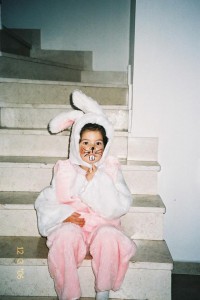

The main characteristic of Purim, the holiday when we remember the near-death experience in Persia, is the dramatic reversal of destiny, going from annonymity to death-row to triumph in an instant. That’s why we dress up, we are one thing, but could very easily be something else. And also, it’s great fun to dress up. Two weeks ago we celebrated Purim, which, in addition to the costumes, also includes bringing gifts of food to your friends and giving charity to the needy.

So what is the moral of this story? King Achashverus was into queens? The more things change, the more they stay the same? We could ask Mahmud Ahmadinedjad, today’s Persian dictator, what he thinks of personal liberty.

In the end, it’s the women who save us?

I like the explanation my friend Debbie came up with, it’s good to dress up, once in a while, and feel what it’s like to be somone else.

Noomi Stahl